While I’ve never taken the time to confirm it, several people have told me that my ejection was one of the rare (some have said the only), out of the envelope ejections where the front seater survived, and the back seater didn’t. In either case, it isn’t something for which I care to be famous.

Early December 1978, Red Flag…I was assigned to the 12TRS out of Bergstrom and we had been at Nellis for over a week. I still remember how high my pucker factor was when we first arrived, but by that time I felt like I was starting to get the feel of how everything worked, and wasn’t quite so anxious when we jumped in the airplane. I do recall being surprised at how much the personality of my WSO changed when we first started flying there. R was one of the Squadron’s Assistant Ops Officers and was about as laid back and easy going as any 20+ year Major could be. He never seemed to get excited about anything…until we got to Nellis. I never did ask him about it, but I’ve often wondered if his time in SEA and the “reality” of Red Flag made his fangs come out a little. Be that as it may, we were working well together and had gone the first week without being “shot down.”

That particular morning was windy and cold, but other than that, there was nothing out of the ordinary. We flew our mission; got the photos of the targets we’d been assigned and were in the process of egressing the area when the RWAR Gear lit up like a Christmas tree. Some serious jinking was in order….immediately. While preparing for Red Flag, we had watched countless hours of video where “jinking” aircraft were tracked visually. I was always struck by how easy it was to predict what they were going to do, especially when they rolled inverted. Everyone seemed to start with a hard turn (either right or left) followed by a wings level pull up, then maybe another hard turn, but eventually they rolled inverted, and…..pulled. Some of the other moves were a bit unpredictable, but as soon as anyone rolled inverted, you knew exactly what they were going to do. Tracking them was about as difficult as clubbing carp in a bathtub. I made up my mind that I wasn’t going to fall prey to that, and began working on something different. When I rolled inverted, I wasn’t going to pull, I was going to push negative g’s. It all worked well in practice, but on that day, the combination of everything going on (adrenalin, pucker factor, inexperience…etc) led to something dramatically different than the ideal escape maneuver.

What I remember most clearly, is feeling like my mind was split in two distinct parts. One was working frantically to try and understand what had happened and how to fix it, the other part was very calmly saying to myself, “Well…so this is what it feels like to die.” Of course all this happened in a matter of seconds, but it seemed like minutes. At some point, I realized that we needed to get out of the airplane because I wasn’t going to save it. I had my right hand still on the stick, and my left hand on the lower ejection seat handle, when it felt like I was being torn apart. I actually thought that the aircraft had hit the ground and was breaking apart.

As I’ve reflected on that moment, I never quite cease to be amazed at how well we were trained, because it’s the only way I can explain how I could go from knowing I was dead, to realizing that I was hanging in my ‘chute and thinking to myself, “OK, now be sure to do a good PLF.” The problem was that we were so low when we ejected that I never got that entire thought through my head and into my body before I hit the ground. If I recall correctly, the accident report calculated that we were somewhere around 135 degrees of bank, under 500’ and over 540 Knots when we ejected.

The next thing I remember was that I was being dragged by my parachute. I reached up several times to try and release the Koch fittings, but I was bouncing so hard along the ground that even trying to locate where they were on the risers was difficult. At one point, I stopped, and had a moment to try and gather my thoughts and get the chute released. It seemed like I was laying there on my back for quite a while and even though I was extremely groggy, I was getting more frustrated by the second because I couldn’t get free. About that time, a strong gust of wind picked up and off I went again, being dragged over rocks and cactus. If I recall correctly, that day the winds were 30-45 knots.

Somehow crystal clarity returned in a flash, and I thought to myself, “If I don’t get out of this thing it’s going to kill me.” I dug in my heels, arched my back to see if I could dig in harder and finally stopped moving. That time I finally got the chute to release and sat up. Once again, training took over, and the first thing I did was turn off the emergency beacon without really even thinking about it. I noticed that the seat kit hadn’t deployed and found out later that it was because it had hit the ground and jammed before the timed sequence for it to open had occurred (more evidence of how low we were). I looked up straight in front of me, and just over the horizon was a pillar of black smoke. For some stupid reason I remember joking to myself, “Gee, I wonder what that is?” The next two things that flashed into my head were trying to find my back seater, and trying to figure out what had happened. A barrage of questions flashed through my head, “Where’s R? What happened? What did I do wrong? Will I lose my wings?” Then it stopped and a moment of thankfulness that I was alive sort of took over.

The next thing I noticed was the fact that both my gloves were missing, as was my left boot and my helmet; all of which were ripped off in the ejection. I could see that my hands were covered with blood and could feel that my hair and my face were also both covered. I tried to pry open the seat kit to get out the radio and signaling mirror. The first so I could talk to someone, the later to try and evaluate the extent of my injuries. It was jammed so hard that I couldn’t get it opened, so I took the knife in my g-suit, cut a piece of parachute and wrapped it around my head. I also noticed my helmet bag and a piece of the tail sitting right next to it.

I actually don’t know how long I sat there on the desert floor, but I eventually saw a Jolly Green approach from my left rear. I waved, and they flew past me heading for the smoke. I saw them land, and a PJ run from the door and then disappear behind a knoll. He then ran back to the helicopter; they took off, turned around and headed toward me. When they touched down, I got up, and began hopping toward them (only one boot and lots of rocks). They told me to sit down and eventually got me into the chopper. The first thing I did was ask how my back-seater was. “We’re not sure, someone else is checking on him,” was the answer I got, but we all knew what he was really saying.

Shortly after I recovered (nothing more serious than lots of scrapes and lots of stitches) I got orders to Kadena, which combined with things like not wanting to admit what all had happened, and a big law suit, kept me from talking to R’s family for several years. When I finally traveled to see them, they were very gracious and kind, though as you can imagine, it was not the easiest conversation I’ve ever had with anyone.

In the course of the accident investigation, the board had a really hard time understanding what had happened. I told them what I had done with the aircraft, and what I had experienced. It started as planned (hard turn, wings level pull, roll inverted and push), but somewhere between the roll inverted and push, the aircraft started pitching and yawing violently. I was told that at after a whole bunch of head scratching, the board called McDonnell Douglass and talked to several of the chief engineers, who immediately said, “Oh sure, that’s divergent roll-coupling,” which is apparently something the Phantom is famous for, at least in the engineering and test pilot circles.

As I understand it, when a Phantom is loaded up (under g’s) and rolled rapidly (with rudder only BTW, to prevent adverse yaw…another bad problem), the difference between the angle of attack and the axis of roll can cause some serious issues, divergent roll-coupling being one of them. The aircraft starts to yaw and pitch, and instead of having those oscillations converge and dampen, they diverge and the aircraft departs controlled flight.

What had apparently happened during the ejection sequence was this: R had pulled the ejection handle first, but because of the flight dynamics of the aircraft, and something amiss with the seat(s) a bunch of things went terribly wrong (or in my case, perhaps right). His canopy came off and hit the tail of the aircraft. Next his seat came off the rail and also hit the tail, killing him instantly. My canopy came off, broke off what was left of the tail, and then my seat slid up the rails and cleared the airplane.

One of the things that helped me keep my act together on the helicopter ride back to Nellis was finding out that our classmate and my Doolie squadron-mate, S was driving the Jolly Green. Hearing his voice and being able to talk to him at that moment in my life was…priceless.

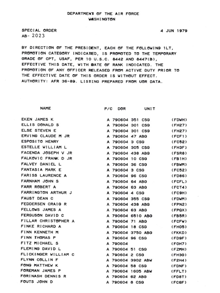

I received a nice thick parcel from the AOG the other day thinking that I would have all sorts of good news to write about, but found out instead that most of the members of the class were promoted to Captain. I’m sure that’s not news to any of you, so I’ll refrain from naming those so honored.

I received a nice thick parcel from the AOG the other day thinking that I would have all sorts of good news to write about, but found out instead that most of the members of the class were promoted to Captain. I’m sure that’s not news to any of you, so I’ll refrain from naming those so honored.